Formal complaints are one of the most stressful aspects of clinical dental practice and are widely recognised as a significant source of professional anxiety among dentists.1 Even when treatment is delivered to an acceptable clinical standard, complaints may still arise owing to misunderstanding, unmet expectations or communication difficulties rather than technical failure.2 For many dentists, the concern is not only the complaint itself but also the time commitment, emotional burden and uncertainty that can result.3

From what I have observed in real clinical settings, the risk of complaints influences everyday professional decisions more than we may openly acknowledge. Some clinicians become increasingly cautious, others avoid complex or time-consuming cases, and many spend additional time explaining, documenting and justifying their decisions as a form of self-protection. In this way, complaints are not only a regulatory or legal issue; they can also affect professional confidence, workflow efficiency and overall job satisfaction.4

This article therefore takes a practical approach to avoiding complaints. Its aim is to explore how artificial intelligence (AI), when used appropriately and responsibly, may help reduce the risk of formal complaints by supporting clearer communication, improved documentation, greater consistency in clinical records and patient-facing information, and enhanced patient understanding while ensuring that the clinician remains fully accountable and in control of all clinical decisions.

The most common reasons that dentists face formal complaints

In most cases, formal complaints in dentistry are not driven by technical failure alone. Instead, they commonly arise from gaps between what the clinician believes has been explained and what the patient has understood.2 Miscommunication, rather than poor clinical skill, is frequently identified as a central factor in patient dissatisfaction and subsequent complaints.4

One of the most common triggers is unmet or unrealistic expectations.3 Patients may agree to a treatment plan without fully appreciating its limitations, risks or possible outcomes. When the final result does not align with what they imagined—even if it is clinically acceptable—dissatisfaction can develop and escalate into a complaint.

In this regard, documentation plays a crucial role. Inadequate or unclear clinical records can make it difficult to demonstrate the rationale behind clinical decisions, particularly if concerns are raised months or years later.2 Even well-justified treatment may appear questionable when records do not clearly reflect the discussion, consent process or alternative options that were considered.

Another frequent contributor to complaints is the perception of not being listened to.1 Patients who feel rushed, unheard or dismissed are more likely to lose trust, especially when complications arise. In such situations, the complaint often reflects a breakdown in the professional relationship rather than a failure of treatment itself.

Understanding these common causes is essential because they highlight an important point: many complaints are linked to communication, clarity and consistency in information, documentation and clinical processes rather than clinical incompetence. These are precisely the areas where carefully and appropriately used AI tools may offer meaningful support—not by replacing the clinician but by strengthening the systems around clinical care.

How AI can help reduce these risks

AI cannot prevent complaints on its own. However, when used thoughtfully, it can support dentists in addressing several of the underlying factors that commonly lead to dissatisfaction. Importantly, AI’s value lies not in replacing professional judgement but in strengthening communication, documentation and consistency within everyday clinical practice.

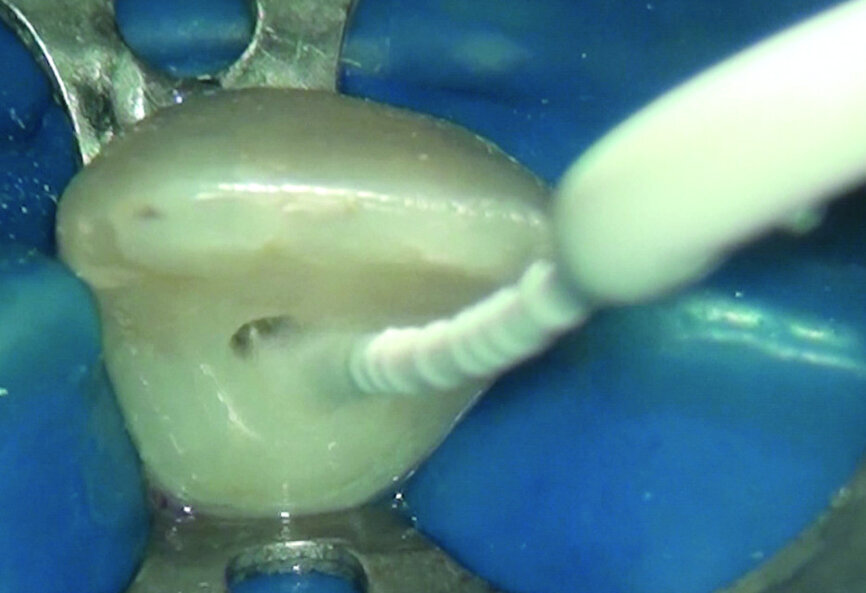

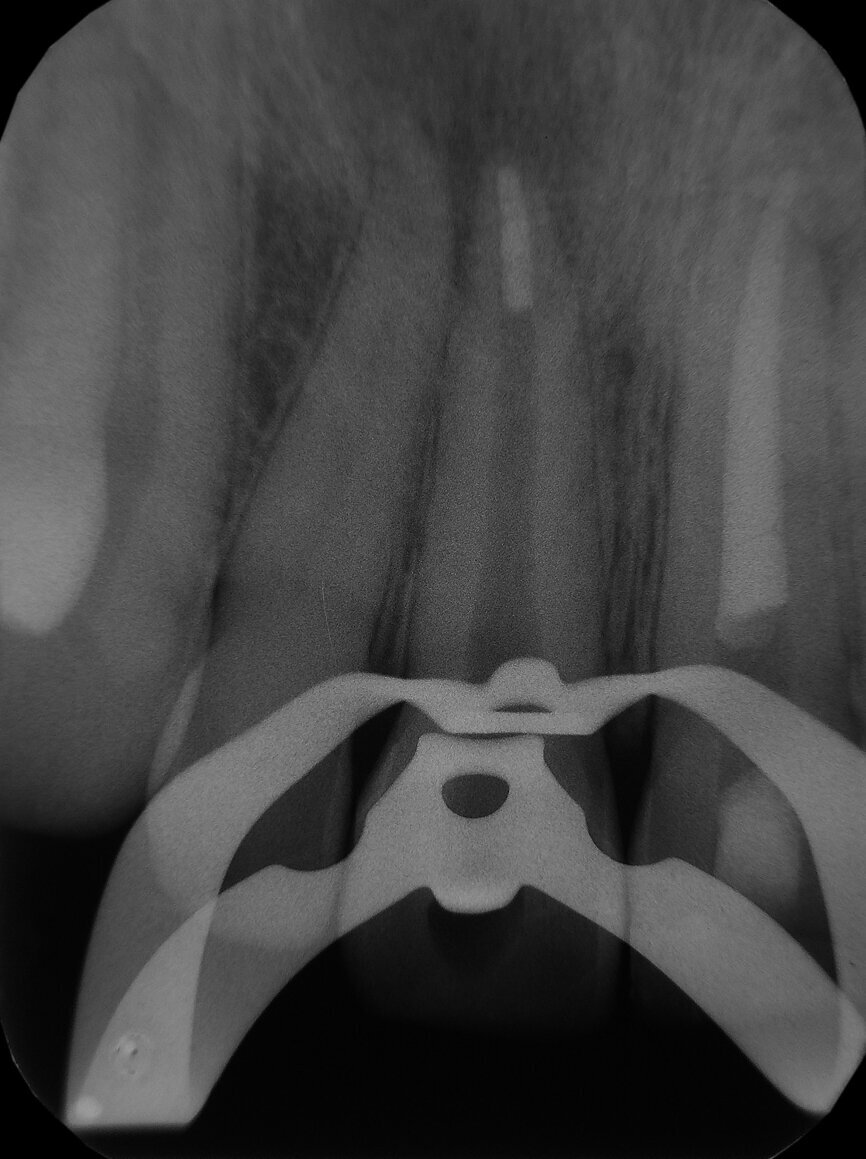

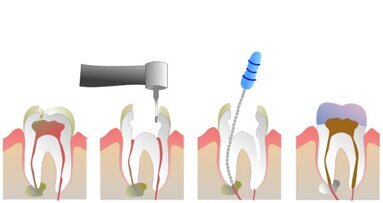

One key area where AI can contribute is communication clarity. AI-assisted tools can help generate structured treatment explanations, summaries and visual aids that support patient understanding. Visual simulations, annotated radiographs and digitally generated treatment previews have been shown to improve patient comprehension and engagement, particularly for complex prosthodontic treatments.5

AI can also enhance documentation quality, which is critical when concerns are raised retrospectively. Automated note-structuring tools, treatment summaries and consent documentation systems can help ensure that discussions, options and decisions are recorded more consistently.2 While the clinician remains responsible for reviewing and approving all records, AI-assisted documentation may reduce omissions caused by time pressure or workload.

Another contribution of AI is improved consistency in decision support. AI systems can analyse clinical data, radiographs and scans in a standardised manner, reducing variability in interpretation and helping clinicians identify issues that may otherwise be overlooked.6 This does not replace clinical reasoning, but it provides an additional layer of support. Crucially, AI outputs must always be interpreted within the clinical context, discussed openly with patients and integrated into shared decision-making rather than presented as definitive answers.

AI tools may also assist in managing patient expectations. By providing realistic visualisations of treatment outcomes—including limitations—AI-supported simulations can help align patient expectations with achievable results.7

Do dental practices need to be fully digital to use AI?

A common misconception is that meaningful use of AI requires a fully digital practice or advanced technical knowledge. In reality, many AI-powered tools integrate seamlessly into existing workflows and can be used alongside conventional systems.5

In practice, many dentists already engage with AI without realising it. Automated radiographic highlighting, structured reporting, digital consent platforms and appointment triage systems often employ AI in the background. Clinicians frequently report that the true simplicity of these tools only becomes apparent once they begin using them.8

Ethics and confidentiality remain central concerns. Responsible use of AI requires adherence to data protection regulations, such as the UK General Data Protection Regulation, which mandates lawful processing, data minimisation and confidentiality.9

Reputable AI platforms increasingly anonymise or pseudonymise patient data, ensuring that individuals cannot be identified from uploaded images or records. Many systems operate on de-identified datasets or process information locally without retaining personal identifiers.10

Ultimately, dental practices do not need to be fully digital to benefit from AI. What is required is professional awareness: understanding what a tool does, how it handles data and where responsibility lies.

How to use AI professionally and safely in daily practice

Using AI safely is less about technology and more about professional behaviour. AI should support clinical practice, not direct it. AI outputs should always be reviewed and interpreted by the clinician. Dentists remain responsible for evaluating information in the context of the individual patient, his or her history, and the clinical findings.2

Transparent communication with patients is essential. Explaining that AI is used to assist assessment or planning—while emphasising that final decisions rest with the clinician—supports trust rather than undermines it.4

Documentation remains critical. When AI contributes to assessment or planning, records should reflect that the dentist reviewed the information and exercised independent judgement.3

It is also important to recognise that not all AI systems perform equally. There are significant differences between freely available tools and subscription-based professional platforms, particularly in analytical depth, reliability, update frequency and clinical relevance. Understanding these differences allows clinicians to interpret outputs appropriately.

The role of indemnity and professional responsibility

From both a regulatory and indemnity perspective, responsibility always remains with the clinician. AI tools do not carry professional accountability and do not replace the dentist’s duty of care.2

Indemnity providers consistently emphasise that defensibility depends on professional judgement, communication and documentation, not on the presence or absence of software.11 Problems arise when AI is relied upon without oversight or when its role is misrepresented to patients.3

A common concern raised by colleagues is that “AI gives the wrong answer”. In most cases, two factors are involved. First, free AI tools and professional subscription platforms operate at very different levels of reliability and refinement. Second, AI responds strictly to the information provided. Incomplete or imprecise prompts often lead to misleading outputs. In these situations, the limitation lies not with the technology but with how it is used.

Conclusion

As this article has shown, complaints are more often linked to communication, expectations, documentation and trust than to technical errors alone. When used with oversight, AI can support dentists in precisely these areas.

Dentists do not need to be fully digital to use AI effectively. What is required is awareness of its limitations, adherence to ethical and data protection principles, and a commitment to remaining accountable for all clinical decisions. Used thoughtfully, AI may help manage professional risk.

Editorial note:

The complete list of references can be found here.

Topics:

Tags:

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

International / International

International / International

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

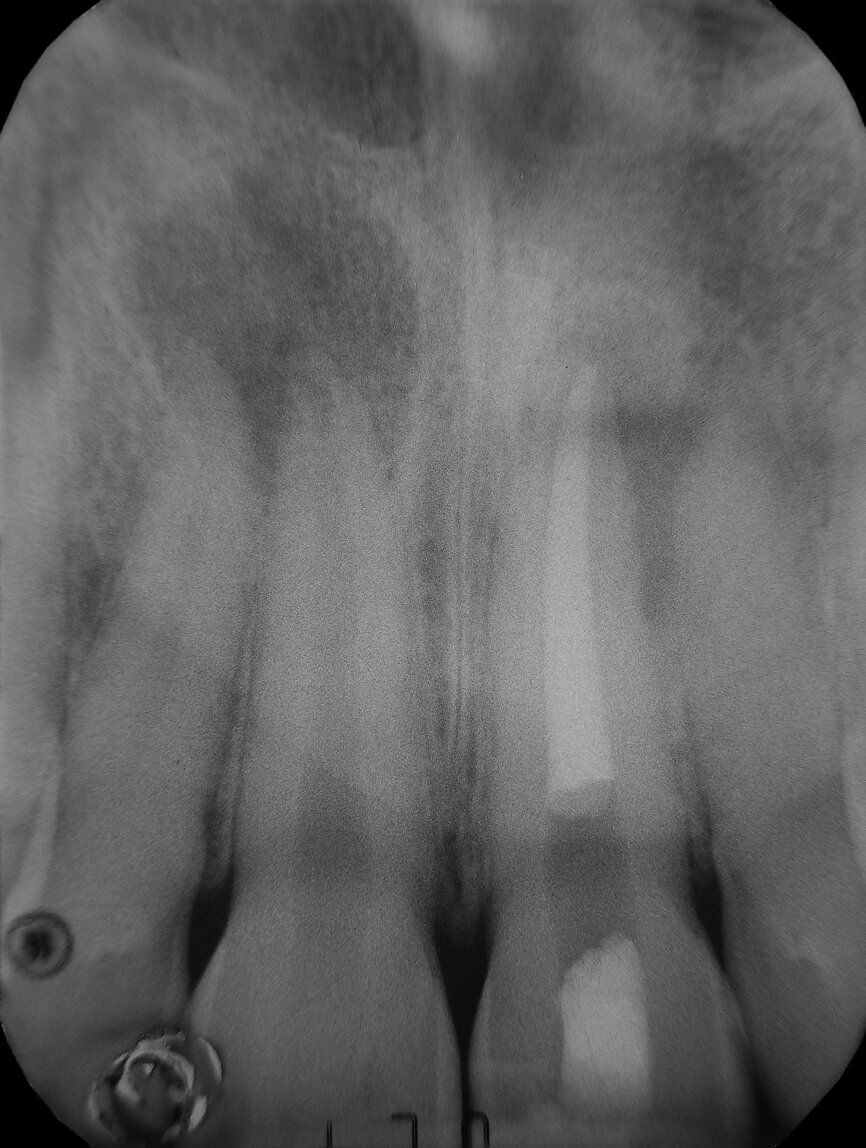

The ultimate reason why root canals fail is bacteria. If our mouths were sterile there would be no decay or infection, and damaged teeth could, in ways, repair themselves. So although we can attribute nearly all root canal failure to the presence of bacteria, I will discuss five common reasons why root canals fail, and why at least four of them are mostly preventable.