BARCELONA, Spain/YORK & LEICESTER, UK/TEL AVIV, Israel: An international team of researchers has conducted a study that gives striking insights into the living conditions and dietary choices of those who lived during the Middle Pleistocene some 300,000–400,000 years ago. By analysing ancient dental plaque samples, the researchers found that our ancestors had healthier eating habits than previously thought and were already exposed to potential respiratory irritants.

The research was conducted by archaeologists from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the University of York, in collaboration with scientists from Tel Aviv University and the University of Leicester.

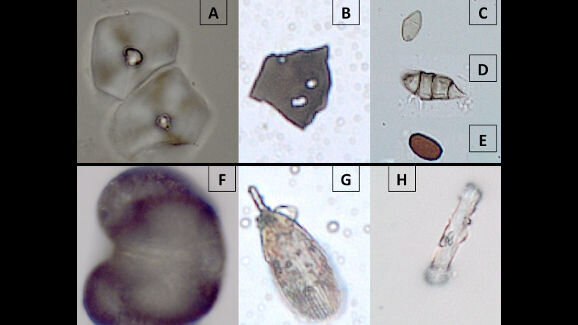

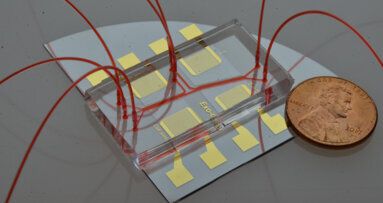

In their study, the researchers extracted samples of plaque from the teeth of three Lower Palaeolithic hominins who lived in Qesem Cave in Israel. By conducting optical and chemical analyses on the plaque, which acts as a store for inhaled and ingested materials, the researchers found starch granules and specific chemical compounds. This comprises the earliest direct evidence for selection and consumption of nutritional plant foods, most probably in the form of nuts or seeds.

Offering a stark contrast to the notion that an early Palaeolithic diet was based largely on meat, these results imply that ancient Palaeolithic hominins were able to sustain a diet that not only was about survival, but also enabled them to thrive and adapt. Making deliberate use of local, nutritional plant resources ensured that their diet fulfilled their physiological requirements. In addition, it suggests that the Palaeolithic hominins had a detailed knowledge of the local ecology.

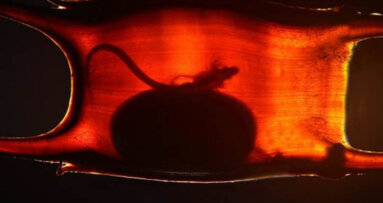

Qesem Cave in Israel contains the world’s earliest secure evidence of deliberate human use of fire. Finding evidence of smoke inhalation in the dental plaque, the researchers detected an early need for methods of smoke management. The study also identified the first evidence of potential respiratory irritants and allergens, including fungal spores and pollen. Moreover, plant fibres and microwear patterns on the teeth point to chewing of raw materials and possibly oral hygiene activities such as tooth picking.

“Our research suggests that Lower Palaeolithic hominins were aware that a range of dietary sources must be consumed in sufficient quantity to ensure optimum survival. The development of internal hearths and successful smoke management also suggests a population that was capable of reason and adaptability,” said Dr Karen Hardy, a research professor at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, an honorary research associate at the University of York and lead author of the study.

“Dental calculus from human teeth of this age has never been studied before, so we had very low expectations because of the age of the plaque,” stated Prof. Ran Barkai of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures. “However, because the cave was sealed for 200,000 years, the teeth we analysed were exceedingly well preserved. These findings are rare—there is no other similar discovery from this time period.”

“What the chemical analysis revealed was the presence of a molecular fossil, which was surprising in material of such an age. This macromolecule essentially preserved the chemical fingerprint of the biomolecules which would have formed some of the original foods consumed, allowing us to provide insights on diet which might not be evident via other means,” Dr Stephen Buckley, a research fellow in the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, explained.

Hardy and her team published research on the dental calculus of Neanderthals from the El Sidrón cave in Spain in 2012, but these dated back only 49,000 years. This current study is of material from several hundreds of thousands of years earlier. “These results represent a significant breakthrough towards a better understanding of the lives and the challenges faced by our early Palaeolithic ancestors, and they offer a fascinating insight into their ecological knowledge and technological capabilities,” Hardy added.

The study, titled “Dental calculus reveals potential respiratory irritants and ingestion of essential plant-based nutrients at Lower Palaeolithic Qesem Cave Israel”, was published online on 18 June in the Quaternary International journal.

YORK, UK: Perhaps unfairly, the teeth of Britons have developed an international reputation for being crooked and aesthetically subpar. Researchers have ...

CAMBRIDGE, UK: Scientists have recently found two primary teeth buried deep in a remote archaeological site in north-eastern Siberia. The discovery has ...

CARDIFF, Wales: A new qualitative study has found that many dental patients in Wales remain unclear about the different roles within National Health Service...

CAMBRIDGE, UK: Two new studies focusing on the evolutionary origin of teeth and of vertebra have provided further evidence of the human connection to marine...

SHEFFIELD, UK: In Western countries like the UK, between 10 and 20 per cent of adolescents undergo orthodontic measures in some form. A recent meta-analysis...

OSWESTRY, UK: The Confidence Monitor survey has recently examined the mental health status of dentists working in the NHS and the private sector. The ...

LONDON, UK: Though the exact number of people who suffer from xerostomia is unclear, some studies estimate that as many as one in five of the population ...

DURHAM, N.C., U.S./BIRMINGHAM, U.K.: Cancers that occur in the back of the mouth or in the upper throat are difficult to spot and, as a result, are often ...

ABERDEEN, Scotland: Head and neck cancer is a highly debilitating disease that has profound consequences for oral function, nutrition, communication and ...

LONDON, England: The National Audit Office (NAO) has reported significant shortcomings in the dental recovery plan launched by the National Health Service ...

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

1:00 am UTC (London)

Dr. Vasiliki Maseli DDS, MS, EdM

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

5:00 pm UTC (London)

Munther Sulieman LDS RCS (Eng) BDS (Lond) MSc PhD

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

6:00 pm UTC (London)

Live webinar

Thu. 5 March 2026

1:30 am UTC (London)

Lancette VanGuilder BS, RDH, PHEDH, CEAS, FADHA

Live webinar

Fri. 6 March 2026

8:00 am UTC (London)

Live webinar

Tue. 10 March 2026

8:00 am UTC (London)

Assoc. Prof. Aaron Davis, Prof. Sarah Baker

Live webinar

Wed. 11 March 2026

12:00 am UTC (London)

Dr. Vasiliki Maseli DDS, MS, EdM

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

International / International

International / International

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register